Deathbed Etiquette: What to Do, and Not Do, When Someone Is Dying

“He died without pain, but the room wasn’t at peace. The love was real; but the noise was constant. Everyone meant well, but the stillness of understanding was missing.”

The final hours carry weight.

In hospice, we enter slowly, observe, hold space, and steady the room.

Yet even then, families and clinicians can feel unsure.

Small gestures echo for years: a whisper, a pause, a glance that says we’re with you. Deathbed presence isn’t instinct; it’s learned.

Steady presence makes a difference. “As her breathing changed, I sat low and said her name before touching her hand. Her daughter exhaled for the first time all day. The room settled.”

I. Why Presence Matters

At the end of life, our task isn’t performance of duty; it’s presence.

Families remember tone, stillness, and whether the room felt safe.

Calm communication and presence correlate with healthier bereavement adjustment (Wright et al., 2008).

Hospice clinicians need to learn to balance action with silence, steadiness with compassion.

NURSE: The Empathy Framework

The N.U.R.S.E. mnemonic was first described by oncologist Dr. Robert Buckman in the early 1990s and later adapted by Foley & Back for palliative and hospice communication.

It provides a repeatable way to respond to emotion before offering information.

Name the emotion: “You look worried.”

Understand by acknowledging cause: “Anyone would feel that way.”

Respect their strength or honesty: “You’ve handled this with courage.”

Support the person: “We’ll get through this day together.”

Explore next steps: “Tell me more about what worries you most.”

Lead with empathy before information.

Quick Rule: Stillness before speech.

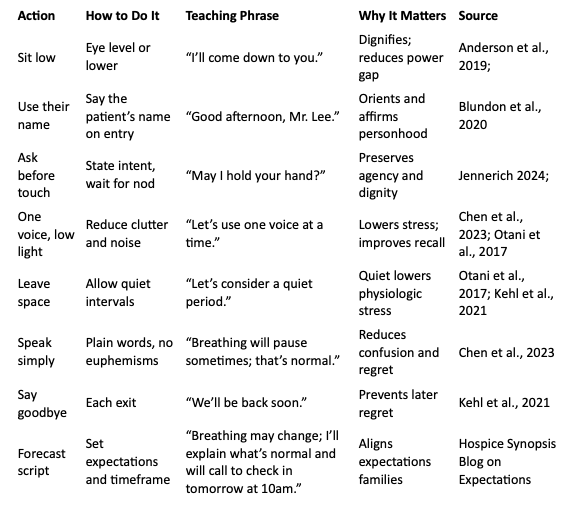

II. What to Do at the Bedside

Speak honestly. Tears are acceptable. So is a silent presence. Just be real.

Remember: Your calm is the intervention; model it first.

III. What Not to Do

Don’t sit on the bed or touch the patient without permission. It’s their space.

Don’t argue or plan logistics in front of the patient. Assume they can hear.

Don’t use euphemisms such as “she’s already gone, this is just the body” while the patient is still alive; plain language prevents confusion.

Don’t overcrowd the space. Rotate visitors as needed, but protect preferences.

Don’t center yourself. If your energy is disruptive, step out and return steady.

Don’t try to predict exact timing. Say instead, “Bodies choose their own time. I expect hours to days now. We’ll stay close.”

IV. Cultural and Spiritual Sensitivity

Traditions vary. A specific gesture may represent honor in one culture, but disrespect in another.

Ask, “What does comfort look like in your family or faith tradition?” Mirror it.

Our humility becomes their permission.

In some cultures, grief fills the room with song; in others, silence is sacred.

Presence begins by reading the room before speaking into it (NCCN 2025.03.31). Observe before adjusting.

Ask, “Is there a prayer, song, or practice you’d like before we adjust anything?”

For people who are non-verbal or unable to respond, presence still matters: say their name, clear loud noise, and offer gentle touch with permission.

V. Family Support and the Vigil Moment

Encourage hydration and breaks. A rested family grieves more steadily (Rabow et al., 2004).

Families often fear missing the moment. We need to normalize rest and rotation: “If you need rest, please rest. We’ll call if anything changes suddenly.” It’s okay to sleep or step out.

Observational research shows some deaths occur during brief absences (Casarett et al., 2012). Presence before death matters more than the instant itself. Coach families that this can happen and is not a failure. Encourage early open conversations when possible.

VI. Educate on When to Call Hospice

Call us if breathing becomes irregular or pauses lengthen; secretions increase; skin mottles or extremities cool; the patient becomes less responsive; or you feel unsure or overwhelmed.

“If you’re not sure what you’re seeing, that’s your cue to call. Interpretation is part of our care.”

VII. Does It Matter Where You Die?

Place matters. Preparation matters more.

Home offers control, hospitals offer access, facilities offer familiarity.

A good death can happen in any of them, but it does not occur by accident.

VIII. Legacy in the Final Hours

Families remember if the room felt peaceful and if their loved one was addressed by name.

If you teach one thing in the final hours, teach this: speak with reverence, be still when needed, and offer a clear chance to say goodbye.

“I remember my first code. I ran toward it and offered only immediate medical interventions. In hospice, I can now make a prolonged impact by intentional presence.”

—Brian H. Black, D.O.

How to Model Presence in 45 Seconds

Enter: pause, scan, sit low.

Say the patient’s name.

Orient: “We’re here to keep you comfortable.”

Align: “What would comfort look like in your family or tradition?”

Forecast: “Breathing may change; I’ll explain what’s normal and when to call.”

Listen for the quiet cues.

Don’t just teach procedures. Teach presence.

Comfort-Care Micro-Checklist (Quick List)

Silence non-essential monitors.

Reposition for easier breathing; elevate head of bed.

Stage mouth-care kit; cue swabs every 1–2 hours.

Treat secretions (anticholinergic if distressing).

Confirm rapid-onset opioid route for dyspnea, along with other comfort meds.

Dim lights; encourage a steady one voice at a time.

Offer chaplain or MSW touch-in.

Document patient and family preferences.

Note the Two-Minute Forecast given to family.

Summary (3-2-1)

3 Key Insights

Presence at the bedside is not instinct—it’s a learned clinical skill that shapes memory, safety, and trust.

Stillness, tone, and honesty often matter more than any medication given in the final hours.

When we teach families and staff what to expect, we replace fear with clarity and transform uncertainty into calm.

2 Actionable Ideas

Integrate a “Deathbed Etiquette” guide into hospice orientation binders.

Add a two-minute “Presence Practice” module to IDG meetings—model how to enter, pause, and forecast at the bedside.

1 Compassionate Call to Action

Don’t just teach procedures or medications.

Teach presence. Practice it every visit. Model it for every team.

Clear communication at the bedside is itself an act of comfort.

Glossary Terms

Deathbed Etiquette – The intentional use of language, presence, and environment to support comfort, dignity, and calm in the final hours of life.

Quiet Clues – Subtle emotional or physiologic signals that indicate the body’s transition toward death. These cues invite the clinician to slow down, listen, and shift from doing to being.

Vigil Moment – A sacred interval near death when presence, stillness, or a single act of kindness brings peace to the dying and those who witness it.

Ritual of Pause – A brief, intentional silence observed immediately after death to honor the person’s life, acknowledge the transition, and center the care team before proceeding with post-death tasks.

Presence Practice (new) – The deliberate rehearsal of bedside behaviors including pausing, lowering tone, and aligning posture—that create calm and trust during decline or dying.

Bibliography (verified and linked)

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. (2008). Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA, 300(14), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.14.1665

Blundon EG, Gallagher RE, Ward LM. (2020). Electroencephalographic evidence of preserved hearing at the end of life. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66007-2

Casarett D, et al. (2012). The surprising legacy of the last goodbye: patterns of death and caregiver presence. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(9), 972–977. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0067

Chen W, Chung JOK, Lam KKW, Molassiotis A. (2023). End-of-life communication strategies for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Palliative Medicine, 37(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221133670

Otani H, et al. (2017). Meaningful communication before death and bereavement outcomes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(3), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.001

Kehl KA, et al. (2021). Caregiver perceptions of the quality of hospice care: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 38(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120963600

Anderson RJ, et al. (2019). Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching end of life: systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliative Medicine, 33(8), 926–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319832458

Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. (2004). Supporting family caregivers at the end of life. JAMA, 291(4), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.4.483

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2025 Mar 31). Palliative Care Guidelines v.2025.03.31. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf

Jennerich AL. (2024). An approach to caring for patients and families of patients dying in the ICU. Chest, 166(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2024.02.015