Turning Death’s Quiet Clues into Coordinated Care

Before prognostic tools, before PPS scores or predictive models, there were quiet observations.

A nurse at the bedside.

A family watching every breath.

A shared sense that something was changing.

Barbara Karnes, RN, captured that moment in Gone From My Sight. It gave families language to understand dying through compassion, pattern, and presence. It became a cornerstone of U.S. hospice culture.

Modern research now lets us expand that wisdom, pairing Karnes’ narrative clarity with cross-condition evidence, physiologic understanding, and language that steadies both families and teams.

I. Research Grounds Intuition: When Science Listens to the Dying

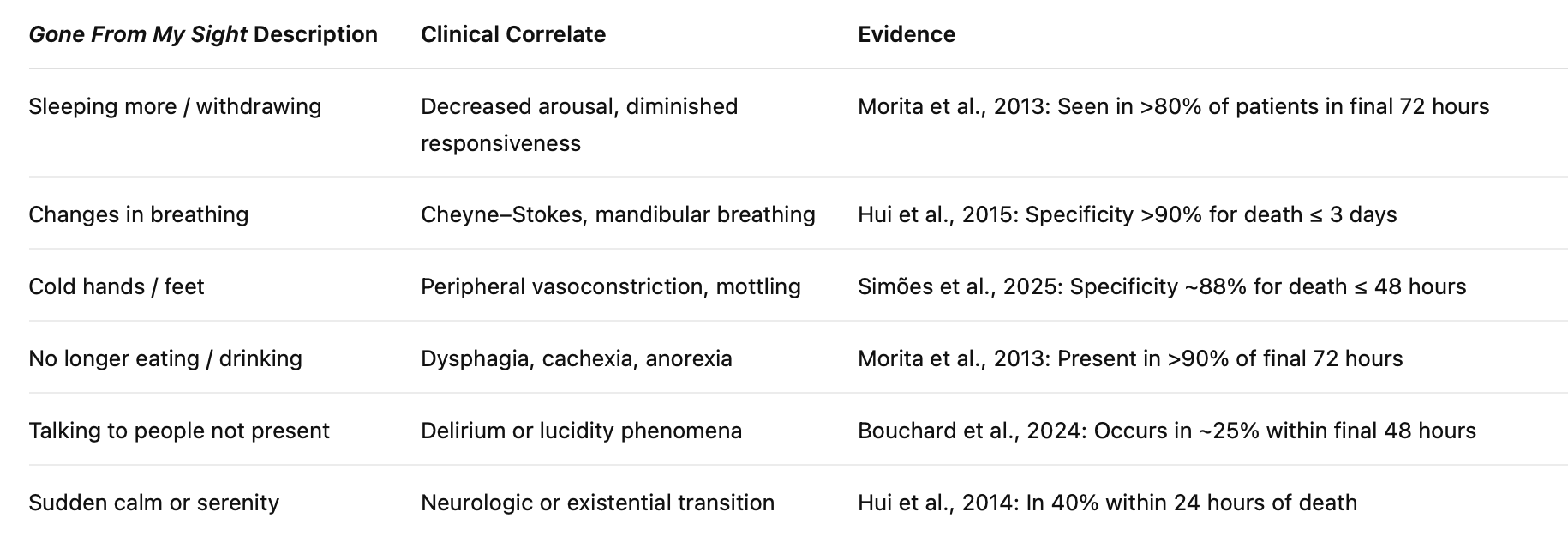

Prospective studies have identified several late signs that, when clustered, carry high specificity—but variable sensitivity—for death within hours to a few days. These include:

pulseless radial artery

mandibular (jaw) breathing

Cheyne–Stokes respirations

non-reactive pupils

nasolabial fold droop

extremity mottling

decreased responsiveness

reduced urine output

These studies confirm what hospice teams have long sensed: patterns emerge near life’s end, but timing remains uncertain.

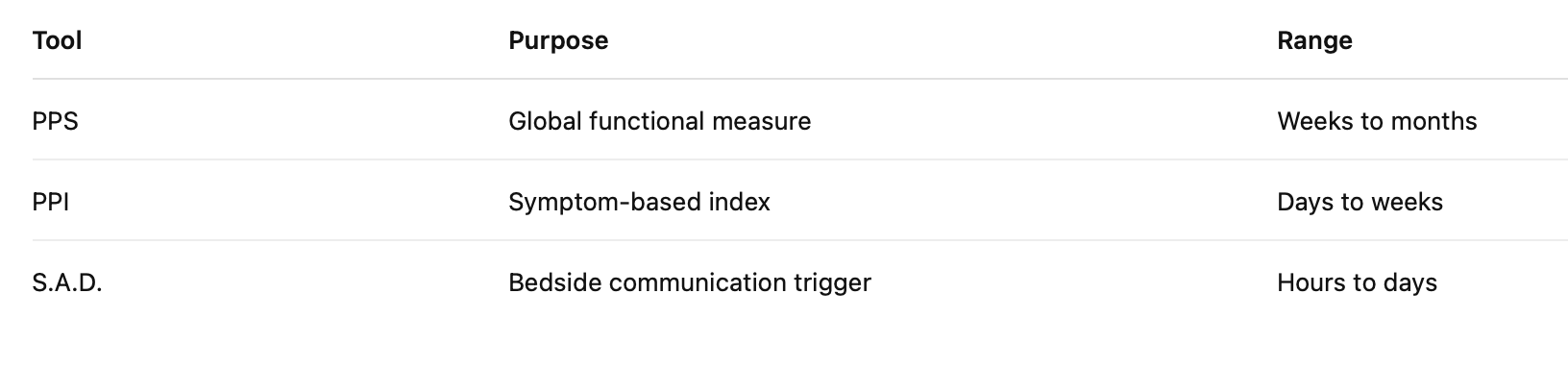

Even validated tools such as the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) and Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) yield probabilistic ranges, not certainties.

Machine learning models echo the same reality: subtle physiologic data can signal decline, but prediction remains error-prone.

The goal is not precision.

The goal is preparation.

When multiple late signs appear, document them carefully. Use them to prompt communication and coordinated readiness, not to forecast an exact moment.

II. Where Stories and Studies Align

Interpretation:

Clusters of signs are specific but not sensitive. Their absence does not rule out nearness to death.

Naming and documenting these physiologic patterns helps families and teams interpret change without overstating certainty.

III. The S.A.D. Framework: Signs, Actions, Days

Clusters of bedside changes often indicate that death may be near.

The S.A.D. Framework turns those observations into coordinated care.

S — Signs

When three or more validated late signs appear together, pause and name them clearly.

A — Actions

Respond as a team: review comfort orders, notify family, align goals of care.

D — Days

Recognize a short window—often hours to days—that calls for presence and calm, not prediction.

What S.A.D. Is For

A bedside communication trigger.

A readiness tool.

A way to make sure no change passes unnoticed or unspoken.

Guardrails:

Specificity is high; sensitivity is limited.

Evidence comes mainly from cancer and inpatient studies.

Do not use S.A.D. to set deadlines or withdraw treatment.

Define signs clearly to reduce inter-rater variation.

Pair observation with caution and compassion.

IV. Where S.A.D. Fits

Use Score + Story:

Combine objective metrics with clinical judgment and family context.

Sample Documentation:

“Late-sign cluster noted (mandibular breathing, mottling, non-reactive pupils). S.A.D. triggered. Team reviewed comfort plan and informed family. Prognosis uncertain. Preparing for an hours-to-days window. PPS 40%. Follow-up in 8 hours.”

Embedding S.A.D. into IDG notes, checklists, and EHR prompts turns observation into coordination.

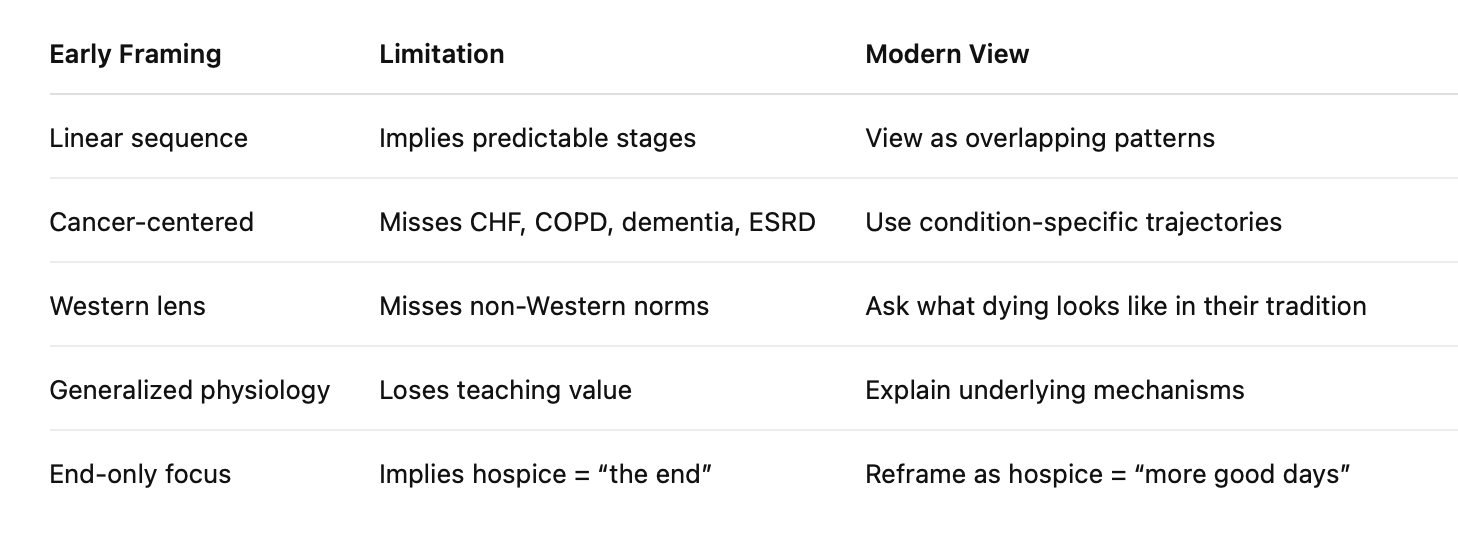

V. From Legacy to Literacy: Expanding the Map

Gone From My Sight remains the cultural backbone of hospice literacy.

Modern evidence maps a broader landscape:

Updated language deepens care without replacing bedside wisdom.

VI. How to Use Quiet Clues in Practice

IDG Teams:

Track late signs weekly. Validate nursing intuition. Include CNA observations.

Clinicians:

Document specific signs (“mandibular breathing noted”). Avoid vague phrasing.

Social Workers:

Support caregiver interpretation and emotional processing.

Chaplains:

Offer presence, ritual, and reflection.

Families:

Learn what to expect and when to call.

Plain-Language Family Script:

“S.A.D. does not mean something is wrong. It means we are noticing the body preparing for rest. ‘Signs, Actions, Days’ is our way of making sure you are supported, medicines are ready, and you have space for what matters most.”

S.A.D. creates coordination.

It does not set a clock.

VII. 3-2-1 Summary

3 Key Insights

Clusters of signs matter more than single findings.

S.A.D. supports readiness without prediction.

Clear, consistent communication builds trust and calm.

2 Actionable Ideas

Add Quiet Clues tracking to IDG reports.

Pair every observed sign with a family conversation note.

1 Compassionate Call to Action

When the body whispers, respond with clarity and calm.

Bibliography

Avati, A., Jung, K., Harman, S., Downing, L., Ng, A., & Shah, N. H. (2018). Improving palliative care with deep learning. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 18(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-018-0677-8

Bernacki, R. E., & Block, S. D. (2014). Communication about serious-illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(12), 1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271

Bouchard, S., Iancu, A., Neamt, E., et al. (2024). Can we make more accurate prognoses during the last days of life? Journal of Palliative Medicine, 27(7), 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2023.0482

Chu, C., White, N., & Stone, P. (2019). Prognostication in palliative care. Clinical Medicine, 19(4), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.19-4-306

Domeisen Benedetti, F., Ostgathe, C., Clark, J., et al. (2013). International palliative care experts’ view on phenomena indicating the last hours and days of life. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(6), 1509–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1677-3

Hancock, K., Clayton, J. M., Parker, S. M., et al. (2007). Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced illness. Palliative Medicine, 21(6), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307080823

Hui, D., Dos Santos, R., Chisholm, G., et al. (2014). Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients: Preliminary findings. The Oncologist, 19(6), 681–687. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0454

Hui, D., Dos Santos, R., Chisholm, G., et al. (2015). Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients: A diagnostic accuracy study. Cancer, 121(6), 960–967. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29048

Hui, D., Hess, K., Mori, M., et al. (2015). A diagnostic model for impending death in cancer patients. Cancer, 121(21), 3914–3921. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29537

Hui, D., Paiva, C. E., Del Fabbro, E., et al. (2019). Prognostication in advanced cancer: Update and directions for future research. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(6), 1973–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04727-y

Jackson, V. A., & Emanuel, L. (2024). Navigating and communicating about serious illness and end of life. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2304436

Lakin, J. R., Block, S. D., Billings, J. A., et al. (2016). Improving communication about serious illness in primary care. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1380–1387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3212

Morita, T., Tsuneto, S., & Shima, Y. (2013). Does physiologic function decline in the final days of life? Palliative Medicine, 27(7), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312461616

Simões, C., Carneiro, R., & Cardoso Teixeira, A. (2025). High-specificity clinical signs of impending death: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 164, 105015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2025.105015