The Global Language of Dying: Euphemisms Across Cultures and What They Teach Us

A family from Ghana yelled: “He joined the ancestors!”

The NP hesitated, unsure how to respond in the moment. Shouldn’t we say died?

As I wrote in [The Cosmic Sleep], euphemisms often delay care. But across cultures, not every metaphor hides. Some phrases are sacred clarity, honoring dying through words families trust.

This moment highlights a deeper tension in global palliative care: euphemisms are not universal evasions but cultural signposts that reveal worldviews on mortality. Research shows that mishandling these phrases can exacerbate mistrust and widen disparities of care, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities (Crawley et al., 2002; Bigger et al., 2025).

Why Cultures “Whisper Differently”

Death taboos: In China or Japan, naming death directly may be considered unlucky.

Ritualized metaphors: “Cross the Jordan” (Christianity), “Return to the sky” (Japan), “Join the ancestors” (African traditions).

Modern & Secular: “Muster out,” “Cashed in his chips,” “Took his last bow.”

Why? To protect dignity, preserve hope, or align dying with cosmology (de Pentheny O’Kelly et al., 2011; Kagawa-Singer & Blackhall, 2001).

These patterns reflect deeper sociocultural values. In many Asian and African traditions, indirectness fosters collective harmony over individual autonomy. Families may specifically request non-disclosure or metaphoric framing to protect patients from distress. When clinicians impose Western norms of direct “truth-telling,” it can feel like cultural erasure (Lambert et al., 2023).

For hospice clinicians, this is not just etiquette, it is language justice: ensuring end-of-life conversations align with cultural values to promote equity in care (Bigger et al., 2025).

A Cross-Cultural Map of Euphemisms

Greek myth: Cross the Styx, rest in the Elysian Fields.

Norse: Enter Valhalla.

African: Join the ancestors.

Indigenous (Iroquois): Enter the longhouse.

Japanese Buddhism: Enter the Pure Land.

Islamic tradition: Called back by God.

Aboriginal Australia: Walk the Dreaming.

Latino Catholic: Se fue con Dios (“He went with God”).

Western popular: Pass away, push up daisies.

The words differ. The impulse is universal.

These metaphors are not denial but orientation. In Indigenous traditions such as the Iroquois “Enter the longhouse,” death is communal continuity. In Islamic traditions, being “called back by God” reflects divine submission. Studies show that when clinicians misinterpret such language as avoidance, families report decreased trust and delayed referrals (Kagawa-Singer & Blackhall, 2001; Green et al., 2018).

Clinical Relevance

A sacred euphemism isn’t avoidance but orientation.

Misstep: Treating “joined the ancestors” as evasion.

Practice: Use clarifiers: “When you say he joined the ancestors, what does that mean for you now?”

If you hear a daughter from Japan say “He returned to the sky.” Ask, “Is that where you imagine him now? And “What does that mean to you.”

This exchange illustrates what scholars call emotionally reflexive labor: the effort clinicians expend to adjust, interpret, and honor cultural cues in real time (Olson et al., 2021; Green et al., 2018). Choosing when to clarify, when to echo, and when to simply listen is not a soft skill. It is clinical work that shapes trust and brings value.

When Euphemisms Help vs. Hurt

Help: Anchor families in ritual, safety, and connection.

Hurt: When clinicians default to vague phrasing in crisis.

Here lies the tension. In Western medicine, clarity often means naming death directly. In many cultures, clarity arrives through metaphor—an intentional way to protect dignity and preserve hope (Kagawa-Singer & Blackhall, 2001).

Our role is not to translate but to discern: Which language honors, and which obscures? (Tulsky et al., 2017).

Building Cultural Competence

Teams need training to distinguish sacred metaphor from clinical avoidance.

Mishandling euphemisms is not neutral—it can deepen mistrust, reduce satisfaction, and reinforce disparities in hospice use. Reviews emphasize language justice as a form of health equity: when clinicians respect linguistic and cultural preferences, patients experience care as safer and more trustworthy (Bigger et al., 2025; Dookie & Martin, 2025).

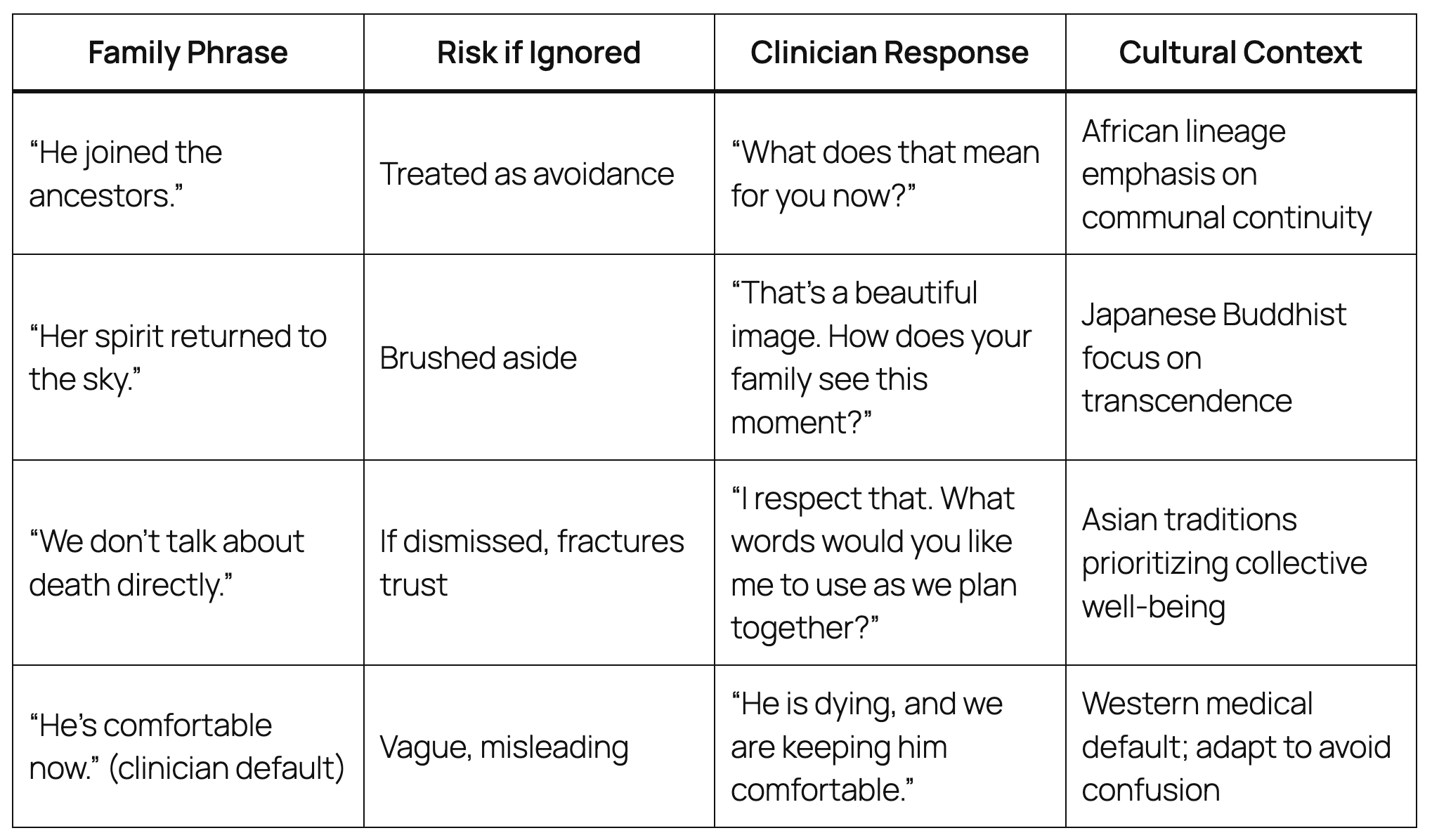

Teaching Tool — Say This / Not That Across Cultures

This is a practical clinical map. For a broader compendium, see the [yaydeath lexicon] and participate in the conversation.

“Every culture whispers death differently. Hospice teams must learn to listen to the meaning behind the phrasing.”

— Brian H. Black

Ultimately, this global lens teaches that euphemisms are portals to understanding—keys to equitable, trauma-informed hospice in a diverse world.

3 Key Insights

Euphemisms are not always avoidance—many are sacred metaphors that honor dying within cultural traditions.

Misinterpreting these phrases as denial can fracture trust and perpetuate inequities in hospice use.

Cultural clarity requires balancing direct communication with respect for metaphors, a practice now recognized as language justice.

2 Actionable Ideas

Train IDG teams to distinguish between vague clinical euphemisms and sacred cultural ones.

Incorporate “Say This / Not That” cross-cultural response tables into staff onboarding and family meeting preparation.

1 Compassionate Call to Action

Listen for meaning before translating. Honor the words families bring to the bedside.

Glossary Terms

Sacred Euphemism (new): A metaphor for death rooted in ritual or culture, used not to avoid but to honor dying.

Cultural Clarity (new): Recognizing and respecting culturally specific language for death while still offering clinical precision.

Language Justice (new): Ensuring patients and families receive end-of-life communication in the terms, metaphors, or languages they recognize as safe and respectful. A core equity practice in hospice care (Bigger et al., 2025).

Bibliography

Allan, K., & Burridge, K. (1991). Euphemism and Dysphemism: Language Used as Shield and Weapon. Oxford University Press.

Ariès, P. (1981). The Hour of Our Death. Knopf.

Barlet, M. H., Barks, M. C., Ubel, P. A., et al. (2022). Characterizing the language used to discuss death in family meetings for critically ill infants. JAMA Network Open, 5(10), e2233722.

Bigger, S. E., Obregon, D., Keinath, C., & Doyon, K. (2025). Language justice as health equity in palliative care: A scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 69(3), 269–288.

Crawley, L. M., et al. (2002). Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA, 287(19), 2518–2521.

de Pentheny O’Kelly, C., Urch, C., & Brown, E. A. (2011). The impact of culture and religion on truth telling at the end of life. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 26(12), 3838–3842.

Dookie, S. P., & Martin, L. (2025). The effect of language discordance on the experience of palliative care: A scoping review. PLOS ONE, 20(4), e0321075.

Green, A., Jerzmanowska, N., Green, M., & Lobb, E. A. (2018). ‘Death is difficult in any language’: Palliative professionals’ experiences with culturally diverse patients. Palliative Medicine, 32(8), 1419–1427.

Kagawa-Singer, M., & Blackhall, L. J. (2001). Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: “You got to go where he lives.” JAMA, 286(23), 2993–3001.

Kellehear, A. (2009). The Study of Dying: From Autonomy to Transformation. Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

Lambert, S., Strickland, K., & Gibson, J. (2023). Cultural considerations at end-of-life: A critical interpretative synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing.

Olson, R. E., Smith, A., & Good, P. (2021). Emotionally reflexive labour in end-of-life communication. Social Science & Medicine, 291, 112928.

Tulsky, J. A., Beach, M. C., Butow, P. N., et al. (2017). A research agenda for communication with serious illness patients. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(9), 1361–1366.